Scientists Discover a Way to Detect One of Diabetes' Most Dangerous Complications Early

PNAS: Japanese scientists have developed a non-invasive method to monitor immune cells in the retina, allowing early detection of inflammation caused by diabetes. The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Diabetic retinopathy is one of the most dangerous complications of diabetes and a leading cause of blindness worldwide. It was previously believed that the condition developed due to damage to the blood vessels in the retina. However, the new study shows that inflammation and cellular dysfunction begin much earlier—before any visible vascular damage occurs.

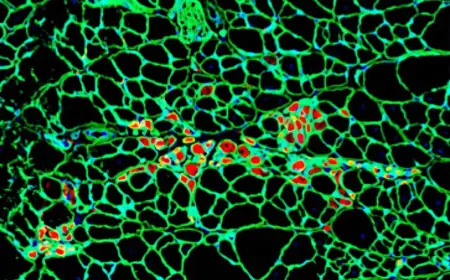

A key role in this process is played by microglia—immune cells that constantly monitor the condition of the retina. In diabetes, these cells become overactive and trigger an inflammatory cascade. Until now, their activity in living organisms had been very difficult to observe.

To overcome this, researchers developed a simple yet effective setup using a head fixation device, specially made contact lenses, and a commercially available lens. This allowed clear, long-term observation of microglia activity in the retinas of live mice, even detecting their smallest movements.

Using this method, scientists discovered that in diabetic mice, microglia began to actively move through the tissue before any visible signs of retinal damage appeared. This suggests that inflammation begins in the very early stages of diabetes, making it a key moment for medical intervention.

Researchers also studied the effect of liraglutide, a drug used to treat type 2 diabetes. It was found to normalize microglial activity in diabetic mice and reduce it in healthy mice—without affecting blood glucose levels.

According to Yoshihisa Tatibana, a neurophysiologist at Kobe University:

“This suggests that liraglutide directly affects microglia through mechanisms independent of blood sugar control.”

The new method could be useful not only for early diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy but also for studying other eye conditions like glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration.

“We hope that in the future, this technology will be used in clinics as a non-invasive tool to diagnose systemic diseases through the eye,” said the researcher.

“The retina could become a unique window into the immune and nervous systems.”